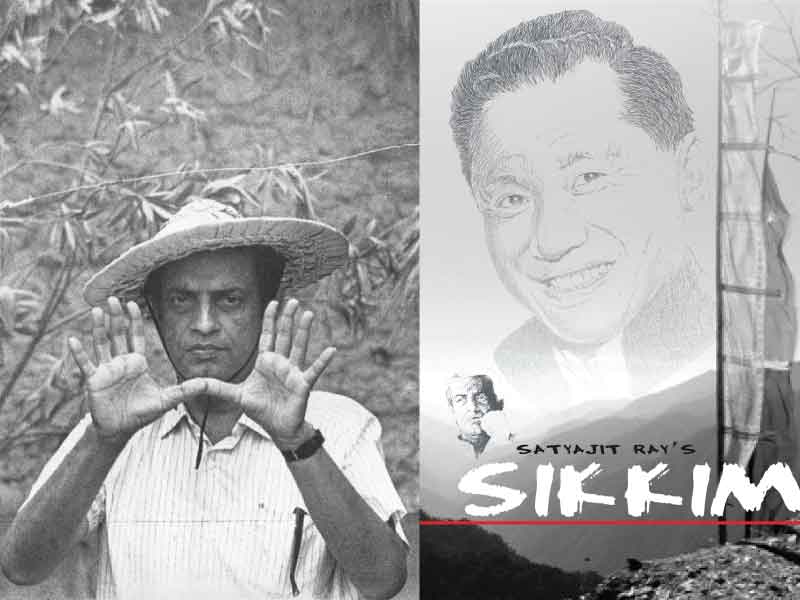

'Sikkim' Documentary film made by Satyajit Ray was banned for 39 years.

Published On: 02 May 2019 | Hollywood | By: Saurabh S Nair

On the occasion of the 98th birth anniversary of the greatest filmmaker of all time, Satyajit Ray. We discuss his documentary which was banned by the Indian government.

Censorship is not an alien term and every art form has been censored or restricted by the higher authority irrespective of any art.

An Art is never finished, only abandoned - Leonardo Di vinci

Even the legendary film auteur, Satyajit Ray has to face the ban of his 1971 documentary film about the state Sikkim.

The film was several times cut, chopped, abandoned and finally banned.

The ban was finally lifted by the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) in September 2010.

The story of the making of the documentary

Sikkim was not a part of India before 1975. It used to be an independent nation, ruled by a Chogyal (or King). In 1971, in a bid to let the world know about their tiny state, the Chogyal Palden Thondhup Namgyal, and his Gyalmo (or Queen Consort) – an American lady by the name of Hope Cooke – hired Satyajit Ray to make a documentary on their nation-state. Ray accepted the assignment and made the film – a beautiful and wholesome depiction of the history, terrain, flora, fauna, art, culture and the people of Sikkim.

Unfortunately, the Chogyal was not happy with the final cut of the film – responding discontentedly to the poverty of the Sikkimese people that Ray had chosen to show in the film. Those scenes were cut out of the film. Then came the annexation of Sikkim by the Indian government. Technically speaking, it was not an annexation. After India attained independence from the British and moved to become a democracy, a freedom movement began to take shape in Sikkim too – with the objective of replacing its monarchy with a democratic government. The Chogyal sought help from India to thumb down the movement, and in the ensuing rush to compete with China, India signed a treaty with the Chogyal in 1950, to grant Sikkim the status of an Indian protectorate.

For two long decades, the ruler of Sikkim staved off India’s continuous attempts of formal annexation, until, in 1975, he gave in and opted to make Sikkim a state of the Indian Republic. The moment Sikkim became a part of India, the Indian government banned Ray’s documentary. And it was not until September 2010 that the documentary resurfaced, when the ban was finally lifted by the Ministry of External Affairs. The film was screened at the Kolkata film festival later that year, and the large audience gathered to watch the film witnessed what a magnificent work of art the master had created.

The film opens with Ray explaining the terrain of Sikkim – a tiny speck in the heart of the mighty Himalayas, which despite their mammoth stature, are nothing but ‘young mountains’ which have hardly stopped growing. The misty mountains, the melting snows giving birth to mighty waterfalls, the lush green valleys, the roaring rivers, and the steep hillsides all create the picture of paradise on earth. Ray then goes on to elaborate upon the rich flora of the land – the hundreds of varieties of orchids and rhododendrons that bloom in a wide range of colors. Then comes the Sikkimese people, and Ray spends a considerable amount of time talking about their origins, their religion, their occupation, and their habits. We learn how Sikkim has become a melting pot, with the Lepchas, the Nepalese, the Bhutias, the Tibetans and even the Indian people all huddled together in this idyllic little heaven of a hill state – each continuing to maintain its own identity.

Sikkim is shown as a happy state, where education is virtually free. Towards the end of the film, Ray chooses to focus on the festivals and celebrations of this idyllic state. One of them is a ceremonial Lama Dance – where masked Lamas dance in circles to celebrate the warding off of evil spirits. At the end of the Tibetan year, the gates to the royal palace grounds are thrown open and a fun fest takes place, where bouts of gambling, sessions of drinking and playful mirth abound. But amidst all this, the disparity in income and well-being is not lost to the discerning eyes of the keen observer.

Sikkim is shown as a happy state, where education is virtually free. Towards the end of the film, Ray chooses to focus on the festivals and celebrations of this idyllic state. One of them is a ceremonial Lama Dance – where masked Lamas dance in circles to celebrate the warding off of evil spirits. At the end of the Tibetan year, the gates to the royal palace grounds are thrown open and a fun fest takes place, where bouts of gambling, sessions of drinking and playful mirth abound. But amidst all this, the disparity in income and well-being is not lost to the discerning eyes of the keen observer.

Soumendu Ray’s camera captures the sights of the land with great affection. Consider a white wall of mist, and a ropeway car slowly emerging out of it, with a worker standing on its edge dangerously, and yet with sure footing – creating a visual marvel, only to be followed by another, more poetic scene of raindrops sliding down a slanted telegraph wire. Or the giggling faces of children as they walk to their school, or of peasants as they arrange their wares on a Sunday morning in the middle of the town market in Gangtok, the mighty deity of Kanchenjungha looking down upon them.

The print which is available is just an extract of the whole documentary. The whole documentary might be more visually stunning than the released version.

Meet the author

A 27 year young writer, graduated in Journalism. A Cinephile who just wants to talk Cinema, walk Cinema and eat Cinema. And obviously write about it.